So, Which Am I?

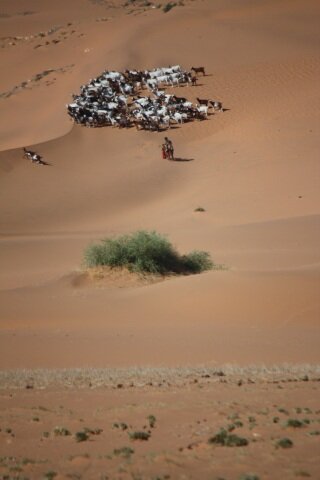

Last week, working with an idea for a new essay, I felt I’d gathered enough of the information I’d gone hunting for, had unearthed enough notes and journal jottings to begin writing, to see where sentences led, or, hopefully, leaped. At the same time, I’d begun my annual trek around the house, scouting what I’d soon need to pack up and load into my car for my migratory drive east to the island. And maybe because the memories of our recent trip to Namibia and Botswana were still playing vividly in my head, not just of varied terrains and landscapes or encounters with wildlife but of different cultures, too, I suddenly found myself asking as I went about my tasks: So which am I? A hunter-gatherer? Or a nomadic pastoralist?An unlikely question, I’ll concede. And somewhat fleeting. More a musing, actually. Yet, over time it stuck, or, rather, images did, no doubt stoked by my attempt to edit and organize the vast number of photographs I’d taken, among them: the Himba nomadic herders of Namibia and the Bushmen hunter-gatherers of Botswana, both of which have survived harsh desert conditions and seemingly unproductive places for 1000s of years.

Also, while doing some research online, in that confluence of happenstance that can land in our laps the odd but somehow useful, I stumbled upon a forum of folks responding to the question: if you were transformed into a pastoralist or a hunter-gatherer, which would you choose and in which ancient or modern culture? Strangely, the answers given tilted to food and diet. Noted in the respondents’ choices were the raw cow milk of the Masai of Eastern Africa, the once plentiful bison of North American Sioux, the salmon and seal of Arctic Inuit (though without mention of fermented seal flipper), and the sheep milk and yak of the Mongols, whose dietary preferences are summed up in an old Mongol expression: “Meat for men, leaves for animals.”

Personally, I like my meat and my salads. Watching me at a local farmer’s market or in a food store’s produce section has prompted my husband to say I forage. Yes, but I do not hunt. And certainly not with a Bushman’s poison-tipped arrows. Nor have I ever owned livestock. And, unlike the Himba, I doubt I’ll ever have to herd thirsty cattle and goats into a river rife with hungry crocs.

On its face, my question and the forum’s are, of course, silly, right? But not silly are the cultures and their traditions, many of them in jeopardy of being lost, that I recently had the privilege to briefly observe. The examples of which, if in some watered down version, I’d encountered while in Namibia and Botswana.

But first, some definitions. For pastoralists, the herding of domesticated animals is their primary activity, both socially and economically, and is usually coupled with mobility. Thus, nomadic pastoralism – an ecological adaptation that provides access to variable, seasonal resources like water and grazing grasses. Hunter-gatherers, also often in some way nomadic, subsist in the wild on food obtained by hunting and foraging.

And here, let’s pause to consider that we all have ancestral linkage to hunter-gatherers, the only form of survival until the “invention” of wide-spread agriculture more than 8,000 years ago. So when I’m foraging among the lettuces in the produce section, I’m loosely linked to my ancient gathering sisters, though a more apt comparison would likely apply were I to head further into Downeast Maine and harvest dulse seaweed in the mid-tidal zone. Or gather edible whelks on the shore in Steuben even if it’s a whole lot easier stopping at Ben’s in Ellsworth for a pint of pickled “wrinkles” that I’m ready to proclaim are more like cooked clams (if a bit chewier) than gum erasers, as some of my pals insist. Here, on the island, several folks keep goats, mostly for their milk to make cheese and yogurt, even soap. But I don’t think fellow islanders would look kindly on them if, as would-be pastoralists, they were to shepherd their flocks to various green spots on the island or, making their way to the mainland, muck up traffic on the bridge.

Clearly our modern world doesn’t smile upon or offer a lot of opportunity to practice the lifestyles of our ancestral forebears. And sadly, as I recently learned, that is increasingly the case even in the remotest regions of Namibia and Botswana.

The Himba, indigenous nomadic pastoralists of which merely 30-50,000 remain, largely reside in the Kunene region of northern Namibia. Still primarily herders, they are now only semi-nomadic. Typically, they inhabit a small circular hamlet of huts around a livestock enclosure or kraal and a central fire, the okuruwo or holy fire that represents their ancestors, intermediaries to the Himba god Mukura. The huts are simple affairs: sapling posts bound together to form a domed roof then plastered in mud and dung or, for the more nomadic, draped with portable textiles, usually old blankets. Most notable about the Himba, however, if measured by the ubiquitous posters, photographs and brochures touting travel to Namibia, is the use of otjize, a mixture of fat and ochre the Himba women spread all over their bodies and hair, and too often renders them mere totemic images.

Unquestionably, the Himba have suffered numerous hardships in Namibia’s quest for independence and the civil war with neighboring Angola, and in periods of genocide and punishing droughts. More recently, their way of life is threatened by plans to build large hydroelectric facilities on the Kunene River that would flood their land, and, more benignly, by mobile schools that educate but also introduce young Himba to modern Western ways. On a positive note, the Namibian government has made it possible for Himba to share in profits that increasing tourism brings. Compromises have been made. Conservancies have been created. Himba now get a small piece of the pie.

As for the Bushmen in Botswana, things look grimmer.

It’s widely accepted that the first people of southern Africa were the KhoiSan – more commonly known as Bushmen. Considered by many geneticists and anthropologists to be the oldest human culture on earth, it’s possible, they claim, that the San are ancestors to us all. Never considered war-like, the Bushmen legacy is one of hunting and gathering, of painting and dancing. So when warrior tribes arrived from the north, they found it easy to push the San from choice spots. Later, cattle farmers gave them a shove. Their livestock fencing greatly reduced Bushmen hunting grounds and cut off migratory routes including access to water. Hundreds of thousands of wild animals died along the fencelines. Since the 1990s, even the Botswana government has gotten in on trying to push out the Bushmen – in the name of eco-tourism no less. Most notable was their forcible removal from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve into permanent settlements in marginal areas outside the Reserve.

Today, fewer than 10,000 Bushmen live in any traditional way. Most have no access to their former way of life – meaning the seasonal movement between passed-down-through-generations “campsites,” often nothing more than large rock overhangs and shallow caves, some handsomely engraved or painted with figures. Meaning men carrying a simple bag of steenbok hide with its quiver of arrows, digging stick, and short spear. And of knowing, in the seemingly barren terrain of vast salt pans or the Kalahari wracked by drought, where to dig for fleshy edible tubers and roots or in what dried elephant dung are recoverable nuts and seeds. And where the women gatherers know how to find wild cucumber and tsamma melon.

Now, sadly, many are “show Bushmen” trotted out for the tourists in traditional dress, carrying bows no longer strung with giraffe sinew and arrowheads no longer made of bone but purchased bits of steel. The more fortunate reside on the private reserves of committed conservationists and traditionally-minded owners (and which I would like to think we were lucky to experience) where local Bushmen can still practice some of their traditions even though they must live part of the year in settlements to fulfill a government mandate that all children be schooled. And where they’re more likely to don Western dress and need the money they earn selling crafts – as do the Himba – fashioned of ostrich egg shells, seeds and beads or painted with powered rock and fat.

By now, it should be obvious that my original question is more than silly. And, in its truest sense, impossible to answer. I’m neither hunter-gatherer nor nomadic pastoralist. My ways are as foreign to Himba and Bushmen as theirs are to me.

Still, if pressed for an answer, I’d go with hunter-gatherer if only by way of what the anthropologists tell me is my passed-down-through-the-millennia inheritance. As a writer, certainly, I forage – for inspiration, ideas, information. In the process, I dig down, unearth. I also hunt: looking, listening, seeing where tracks lead. And, though cave painting is not part of my oeuvre, I attempt to express myself artistically.

But as I pack my car for my annual trek east, I also acknowledge the nomadic in me. True, I have no livestock to shepherd enroute, not even my long-time travel companion, our late dog Ben. And surely, as I survey my many – too many – accumulations I plan to squeeze into my car, I am unlike the possession-eschewing Himba.

Plus, trust me, unlike the Himba women, I cannot walk three steps with a single object balanced on my head. Not even an old blanket.