The Where of It

As I write this, I’m sitting at a small desk in a western-facing window of our 21st floor Chicago apartment. My view, a now familiar one, is a swath of the city waking up, of tall buildings near and far, of rooftops, treetops and chimneys, and, far below, buses and cars and a few people walking their dogs. A little over a year ago, I hunkered down, as I had for the previous 16 years, at a desk in our Evanston home, in front of a large window looking out to a small patch of garden, the brick wall of our garage, the limbs of a leafy maple branching above. A month from now, after my annual migration to our Maine island home, I’ll plunk down at a desk in a place new to me, whose only occupants at the moment are a pair of carpenters busy with saws, hammers, and cut, fragrant lummber.

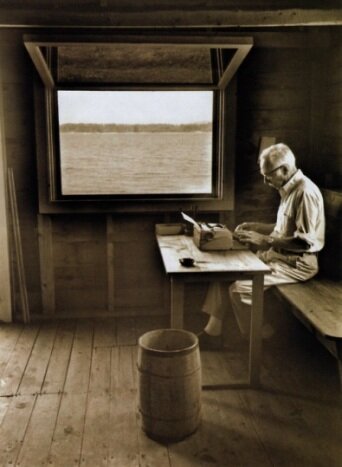

There, a long-held dream is materializing: a writing place all my own. A dedicated space. “A room of one’s own” that Virginia Woolf proclaimed decades ago was especially necessary for women writers. But rather than a room tucked into the confines of a larger house – or apartment – my new place is separate, detached, independently rooted into the landscape. In my case, in a small clearing in the woods adjacent to our house.

Not that such a place is necessary, of course. For years, in our Evanston house and now in this apartment, I’ve written in a spare bedroom appropriated as my “office” but where, too, the occasional overnight guest bunked down. And where my various manuscripts, drafts, files, notebooks and books shared space with checkbooks, ledgers, invoices, legal documents, construction plans, tax preparation forms, family photograph albums, and all the other myriad flotsam of household management. Even this, I know, can be considered a luxury. Consider Jane Austen who wrote in a busy sitting room in a small English cottage shared with her mother, sister, a friend and a steady stream of visitors. Fortunately, her family respected her work and Austen’s sister shouldered much of the house-running burden, as acknowledged by the novelist who once wrote: “Composition seems to me impossible with a head full of joints of mutton and doses of rhubarb.” Writer Toni Morrison, for years juggling 9-to-5 jobs and young children, spent pre-dawn hours at a kitchen table. Maya Angelou occasionally sought the refuge of a motel room.

Many writers have long opted to set up shop at a table in a library. Others, not so much moved by necessity but preference, seek busier public spaces, like coffee shops. I have never been one of them. I prefer to be alone and without much background noise, particularly music with rhythmic insistences of its own. Oh, I certainly go “public” when things are already brewing, usually in the afternoon after, if I’m lucky, a few good hours at my desk, when I’m composing, re-writing in my head. It’s then I take a walk or go for a run. I’m propelled out by appointments, meetings, and social engagements. Or I attend to errands, maybe shop for dinner, and, in casual greetings to strangers while newly composed sentences are looping in and out of my noggin, I, like Angelou, “pretend to be normal.

But I’m definitely not in the camp of Richard Russo who, in an interview, claimed that writing in a public place such as a diner is a “less lonely way to write,” and where you know “when the phone rings, it’s not for you.” Neither can I ally with Eudora Welty who once boasted that she found it possible to write almost anywhere, although, admittedly, she preferred home because it’s “more convenient for an early riser and it’s the only place where you can keep out interruptions.” Or try to.

Working at home also enables a transition from waking to working and sliding into the writing to be quick and, usually, unremarkable – maybe nothing more than the simple choreography of getting out of bed, switching on the coffee maker and stumbling toward the desk. A dance I know well, but is most often embellished with additional steps: making the bed, getting dressed, reading the New York Times op-eds while slurping some yogurt, maybe emptying the dishwasher. Danger looms, however, if I first check emails or perform what writer William Gibson calls our “internet ablutions.”

As quoted by Alexandra Enders in “The Importance of Place: Where Writers Write and Why,” the late poet Robert Creeley who required “a kind of secure quiet,” once observed: “The necessary environment is that which secures the artist in the way that lets him be in the world in a most fruitful manner.” The kind of place where a writer can access creativity, is able to incorporate memory, imagination, and curiosity, while negotiating how much protection such a space needs from everyday demands.

A place where we park our butts in the chair and try to say or shout something. Meaning it’s as much psychic and physical. Meaning the actual where-and-what of a place has less to do with the whole enterprise than persistence and diligence and just showing up at your desk wherever that may be. “A writer who waits for ideal conditions under which to work will die without putting a word on paper,” proclaimed E.B. White.

Of course it’s tempting to believe that if we have or are in the right place then surely we’ll write our best, our output will astonishingly pour forth. Many of my non-writer pals think our Maine island must surely be a superior place to work. Yes, in many ways, it offers more opportunities for solitude and reflection, and most days there is a sense that time doesn’t move at quite the same pace. But it is not free of distractions or demands -- of the sometimes seemingly endless lists of chores and tasks, of a short summer squeezed with houseguests, a burgeoning number of friends, an expanding garden, the seasonal plethora of gallery openings, performances, lectures, concerts and readings. Nor does the beauty of the place necessarily help. I can easily yield to the beguiling lure of the tides tossing new treasure on the shore, of trails leading into the mossy woods. There are days that, like a ship adrift, I can be lost in reverie staring out at the ever-changing Bay. Days when the pencil isn’t lifted, the computer sits untouched. A confession: writing slips further down the list when the sun is out. Plus, no matter where we’re parked, writing is hard. It can be tedious and boring when tackling the necessary daily increments that, it’s hoped, will open, lead somewhere or to something really engaging. Days when, seriously, I’d rather iron!

Now, as I get ready for my annual migratory drive east to the island, I’m wondering how my new writing place will change things. I don’t even know yet what to call it. Hut or shack, though attractively humble, don’t work – certainly not in the Henry Beston or Thoreau-and-Walden sense. Shall I stick with what was proposed to the island planning board? A writer’s workshop? A moniker that more than cabin or studio suggested here was a structure requiring electric power, yes, but didn’t hint at any requisite mucking things up with leach field and septic nor in its potential use require closer shoreland zoning scrutiny. Office no longer fits – a name I needed years ago as currency when I left the business world and wanted to legitimize my new endeavors.

How, now, might my daily routines be altered? My practiced habits of order? Oh, I’ll still be a “morning person.” But what if I wake especially early and want to go to work? Will I make the short trip outside, especially in the cold? Where, coffee mug in hand, will I read the hard-copied sentences of what I wrote the day before, a favorite way to start? Surely, distractions will still exist, but will I find more of them under my nose before heading out? How will I recognize my procrastination – the suddenly necessary need to re-arrange chairs, empty the waste can, straighten my desktop, clean the computer screen, resharpen pencils when I’m ready to or, rather, am sidling up to launching a new project or facing a looming deadline? I’ve yet to know what my new view will be like although in a nor’easter this winter, a seemingly healthy spruce crashed down, as though obligingly opening things up to the Bay beyond. And what now of expectations? Of new demands? That now, I must get the work done. Not having the right place is no longer an excuse.

I do know this: it will be more of a journey. A welcome one, I think. I will no longer take a few steps down the hall, all that’s been required in this apartment or our previous house. The walk now, even if brief, will likely seem more of a passage, akin to what I’ve experienced over the years when attending a handful of artists’ colonies. When you arrive at a place dedicated to your aim to work deliberately and intentionally. When you arrive at a threshold, open the door – your door – and, crossing over, hear the click of it shutting behind you. That click a type of pattern-recognition that acknowledges I’ve arrived. I’m here. Ready.